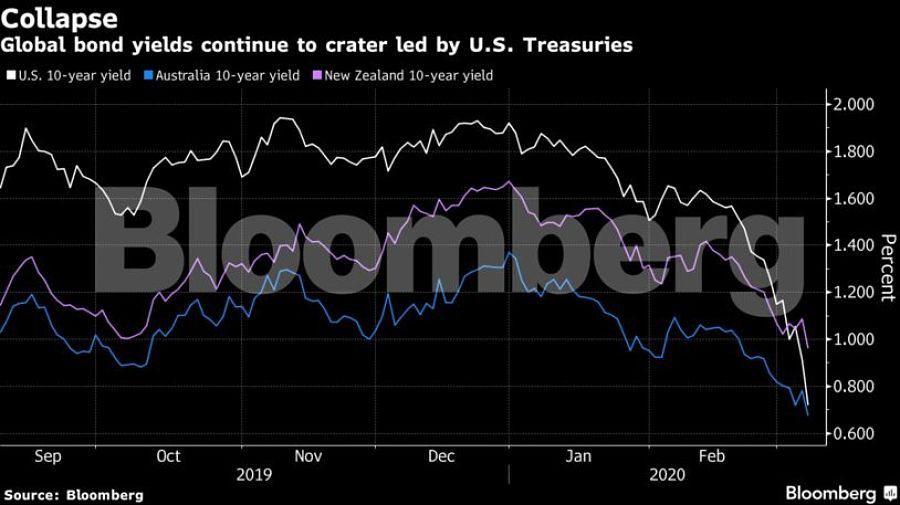

Sovereign bonds are emphatically demonstrating their appeal as a last refuge for investors spooked by another global crisis, this time sparked by the economic fallout from the coronavirus.

Government debt racked up further historic milestones Friday, with 30-year U.S. yields set for their biggest slide since 2009 and China’s 10-year rates falling to the lowest since the country was battling deflation in 2002. German yields sank to a record and the rate on short-dated U.K. debt neared 0% as the market braces for more stimulus from central banks.

The moves were so powerful they risk stoking alarm in other markets, from equities to credit. The unusually large swing in Treasuries pulled down equity benchmarks across Asia and Europe. Where yields bottom from here is anyone’s guess.

Advertisement

“Zero percent yields are no barrier to any bond market in the developed world right now,” said Shaun Roache, chief Asia-Pacific economist at S&P Global Ratings. “It’s an insane market — investors are redefining the idea of risk distribution.”

News on the coronavirus epidemic and policy makers’ responses — including the Federal Reserve’s emergency 50-basis-point rate cut Tuesday — have swung stocks one way and the other. But for bonds, it’s essentially been a one-way street.

Ten-year Treasury yields, arguably the single most powerful global financial-market metric, have cratered in the past three weeks, down about 80 basis points. That’s a scale unprecedented since the aftermath of the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc. in 2008.

Ten-year Treasuries were at 0.73% as of 3:20 p.m. Friday in London, with 30-year Treasuries at 1.29%. China’s 10-year notes yielded 2.63%, against about 3.15% at the start of the year. Australian 10-year bonds have lost about half the nominal yield they had just weeks ago, as that market anticipates the introduction of quantitative easing.

Sharp gains in U.S. long-bond futures caused circuit breakers to kick in on three separate occasions, briefly halting trading.

Mr. Roache said investors are now discounting a return of QE by the Fed and an expansion in Bank of Japan asset purchases. Money markets are pricing about a 90% possibility that the European Central Bank will lower its deposit rate by 10 basis points next week, or boost asset purchases.

But the trend has been as inexorable as the spread of the coronavirus itself, with new waves of infections and markdowns in growth forecasts driving fresh inflows to risk-free securities.

It’s driven the global supply of bonds with negative yields to $14.4 trillion, up by well over $3 trillion since mid-January, before the epidemic became apparent in central China.

Last August’s record — almost $17 trillion amid a rough patch in the U.S.-China trade war — stands to be blown away should a swathe of the Treasury market see nominal yields drop below zero for the first time. Two-year rates have less than half a percentage point remaining.

Race to zero

In the U.K. too, two-year yields at one point Friday morning hovered just 10 basis points above 0%.

“The race to zero is just flying off the handle,” said Vishnu Varathan, head of economics and strategy at Mizuho Bank Ltd. “Trying to draw a line in the sand for 10-year yields when markets are slammed by fanatical hopes of Fed action and pandemic fears in turn may be a fool’s errand.”

It’s all been a dramatic showcase for the benefits of bonds as a hedge in portfolios, after that traditional allocation strategy faced questions less than two years ago. The Bloomberg Barclays Global Aggregate index of bonds has returned 3.3% since the year began, versus about minus 9% for the MSCI All Country World Index of stocks. Gold, another once-maligned hedge, is up 11%.